In a continuation of last week’s article, ” Stock Selection Process, Simplified” we are going to revisit a concept which famed investor Warren Buffett outlined in a talk he gave at Columbia Business School in the late 1980s. Revolutionary for both its time and perhaps moreso today in a world of ever-decreasing “investor” timeframes, the notion of of an equity bond might be the single best method of analysis when analyzing potential individual long term equity investments. Before we dive in, some will undoubetedly need to remove their speculator hat, and replace it with their investor hat. If unsure of the difference, allow Benjamin Graham to help:

“The most realistic distinction between the investor and the speculator is found in their attitude toward stock-market movements. The speculator’s primary interest lies in anticipating and profiting from market fluctuations. The investor’s primary interest lies in acquiring and holding suitable securities at suitable prices.”

Seth Klarman in his classic work “Margin of Safety” described a speculator’s activities as one who is frequently “guessing what the next guessor is going to guess.” Fairly comical, but extremely true. Now that we have that differentiation out of the way, let’s get to it.

The concept of an equity bond begins by a fundamental understanding of a risk free security. Most investors accept that the U.S. 10 Year Treasury Rate is taken as the “risk free” rate. That is because the repayment of both principal as well as the coupon rate is backed by the full faith and credit of the United States Government and its ability to tax citizens. As I write, the 10 year is yielding approximately four percent.

A fixed income (bond) investor interested in purchasing a 10 year U.S. Government bond is essentially providing a loan to the government. In return, the issuer (U.S. Government) promises to pay back the principal plus a stated rate of interest each year, generally paid out semiannually. In purchasing this bond, you’re effectively lending the government $10,000. Every year for the next ten years, the government will owe you 4% of that $10,000 ($400 annually or $200 every 6 months) as an interest payment, also known as a coupon payment. In addition to the $400 coupon payment you receive yearly, the government will also have to pay you back the full $10,000 when the bond matures (in this case, at the 10-year mark). Simple enough.

Buffett took this concept of a risk free investment and applied it to both buying entire businesses, as well as purchasing partial interest in a company via common equity shares in the stock market. But how can a common equity investment act as a bond? Last week I mentioned that there are no guarantees when it comes to individual stock investment (nor guarantees when it comes to index funds for that matter). While it is true that common equity investments offer no such guarantee, there are those select cases of businesses available to common shareholders that over time, get pretty close. And due to this lack of guarantee, also offer a much more attractive upside for the extra risk being taken. The question then of course is how do we find such companies?

The answer lies therein those companies demonstrating a history of superior earnings growth and stability put in place by their durable competitive advantage. This durable competitive advantage manifests itself in powerful underlying economics of businesses which allow them to consistently grow their pretax earnings almost without fail, year after year. These unique businesses have proven themselves to have a durable moat acting as a fortress around their castles which are constantly being barraged by competitive forces in a war we refer to as “capitalism.” As their pretax earnings grow year after year, so do the prices of their common stock as the market acknowledges the increased value of their underlying businesses. Those pretax earnings are Buffett’s version of a coupon or interest payment from a risk free security, with a very important difference: they are growing as opposed to fixed. Let’s see how this works using a well known Buffett investment in Coca Cola.

In the late 1980s, Warren began acquiring shares of Coke around $6.50 per share. At that time Coke had earnings per share of roughly 70 cents. If you will remember from last week’s post, this is where earning’s yield is useful. Knowing both EPS and share price allows us a simple calculation which can serve as the starting point for an initial investment. Taking EPS of .70c and dividing by an average purchase price of $6.50 gives us an earning’s yield of approximately 9.3%. Buffett considered this to be his “IRR” or initial rate of return (not to be confused with internal rate of return used in corporate finance in capital allocation decisions).

If you know your market history, you know that the risk free rate was much different in the late 1980s when Buffett made his initial Coca Cola investment than it is today. Yields on the 10 year bond were anywhere between 8-10%. With this “hurdle rate” as high as 10%, at the outset Buffett’s investment in Coke didn’t look like much of a value at all if you are simply comparing the initial earning’s yield of his Coke purchase to the ten year risk free rate. But isn’t Warren known as the greatest “value investor” history has ever known?

While at first glance the initial purchase of Coke shares in the late 1980s didn’t appear competitive in terms of only earning’s yield, this is where the critical difference between investing in common equity and fixed coupon rates comes in. Coca Cola as a business had earnings power due to their competitive advantage. Warren noticed that Coke had been growing earnings at roughly 15% year over year for some time. This meant that the numerator in the earning’s yield equation (EPS) might be projected to continue this growth years into the future at a rate roughly similar to the recent past’s 15%, either through increased business, expansion of operations, new products, or share repurchases. This projected growth over time is what makes investment in these special businesses powerful wealth building vehicles. Or as Buffett called them, “equity bonds.”

So how did Buffett do on his original investment in the Coke “equity bonds?” By 2007 Coca Cola’s EPS had grown at an annual rate of just under 10% falling short of Warren’s projections of close to 15%. Even the best to have ever done it don’t get things perfect. And there is no need to. By 2007 EPS had grown to $3.96 per share against his original investment of $6.50 per share. The astute reader is already running the math in their head (3.96/6.50) which equates to a current pretax yield of 60%. In 2007 Buffett began selling some of his original shares he acquired at $6.50 per share at a price of… you guessed it, $60 per share.

How though did “the market” know to price the shares around $60? When given time, the stock market will eventually track the increase in specific companies’ underlying values due to the possibility of a leveraged buyout offer. If a company has little debt, a history of consistent earnings stability, and its stock price falls low enough, another company can come in and buy it, financing the purchase with the earnings of the acquired company. This fundamental “secret” is the very same method of analysis Buffett has used time and time again to create billions of dollars of wealth for shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway. The secret can be summed up as follows:

If we buy companies with a durable competitive advantage and a history of superior earnings stability and growth, the stock market over time will price the shares (or equity bonds) at a level reflecting the value of its earnings yield relative to the yield on longer term risk free bonds.

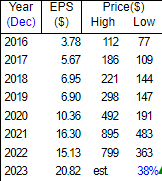

Because we can’t go back in time and participate along with Buffett in his $6.50 per share Coke purchase, we have to find our own. Where do we start? If you followed along last week, you may have a list of companies with a strong history of high ROIC or ROE. That is a great place to begin as these businesses have proven themselves to have some sort of moat or durable competitive advantage. You might notice that a number of names from that list have earnings history that looks something like this:

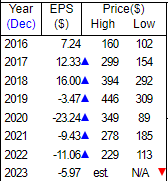

Contrast the above earnings growth and stability with a company that appears to lack a durable competitive advantage:

It becomes clear which of the two may fit Buffett’s “equity bond” profile.

I use a version of the very same approach outlined above in building quality client portfolios at JSPM for long term investment appreciation. I didn’t invent it, but rather followed in the footsteps of probably the greatest investor who has ever lived. To use Buffett’s own words, “First the innovator, then the imitator, and then the idiot.” My job is focused around imitation as opposed to innovation, all the while attempting to steer clear of being the idiot. 🙂

If you need assistance in long term investment management, JSPM LLC offers a suite of strategies designed with your unique goals in mind. We manage assets for a wide range of investors, handle 401k rollovers, individual and joint accounts, and more. Don’t hesitate to reach out or visit us at jspmllc.com or myportfoliofix.com.

Thanks for reading and see you back here next week!

Trent J. Smalley, CMT

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of

investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance

of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product made reference to directly or indirectly in this

newsletter (article), will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s),

or be suitable for your portfolio. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions, the content

may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any

discussion or information contained in this newsletter (article) serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute

for, personalized investment advice from JSPM LLC. To the extent that a reader has any

questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation,

he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. A copy of our current

written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available for review upon review.